Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC)

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is rare but very aggressive. It looks and acts differently than other breast cancers, and is more difficult to treat because it spreads quickly from the breast to the lymph nodes and other organs. In most cases, IBC has already metastasized by the time it is discovered.

Inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) is rare but very aggressive. It looks and acts differently than other breast cancers, and is more difficult to treat because it spreads quickly from the breast to the lymph nodes and other organs. In most cases, IBC has already metastasized by the time it is discovered.

Facts about IBC:

- Accounts for less than 5 percent of all breast cancers diagnosed in the U.S.

- Develops more often in younger women than other breast cancers.

- Occurs more frequently and at a younger age in African Americans than in Caucasians and other ethnic groups.

- May be associated with a family history of breast cancer (limited studies have been inconclusive).

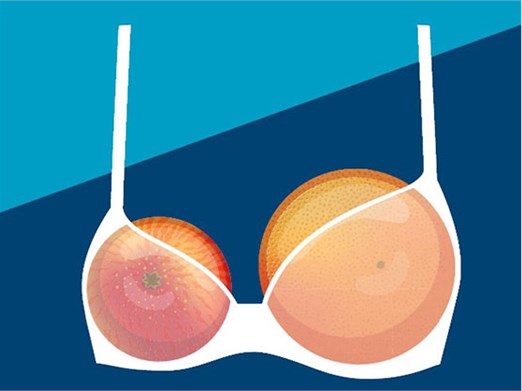

IBC is difficult to diagnose, because its symptoms are often mistaken for infection or other benign breast conditions. The breast may appear warm, heavy, itchy or tender. The breast skin may look thickened, pitted like the peel of an orange, or red—a result of cancerous cells clogging the lymph vessels in the breast skin. Some women may have bruising on the breast that does not heal. The nipple may become flat or inverted and may have a discharge, and the natural color of the areola may change. The breast may swell suddenly; sometimes as much as a cup size in just a few days. Lymph nodes under the arm or above the collarbone may be swollen.

IBC is infrequently found by mammogram or ultrasound. About half of women with IBC have a lump or a mass in their breast, but it may be difficult to feel since the breast is often bigger and harder than normal. IBC may cause aching or stabbing pains in the breast, contrary to the popular belief that “breast cancer doesn’t hurt.”

Many doctors have never actually encountered or treated IBC, and often misdiagnose the characteristic swelling and redness as symptoms of a breast infection or a rash. IBC, however, does not respond to antibiotics. Once symptoms appear, IBC is usually confirmed by biopsy; a mammogram, MRI, or ultrasound may also be used. A chest X-ray, CT scan, bone scan and other additional tests may be performed to determine the extent of the metastasis.

IBC is treated aggressively: several rounds of chemotherapy, hormone therapy if your tumor is hormone-dependent, or both, followed by mastectomy with lymph node dissection and radiation. The exact treatment prescribed varies depending on the individual. If your IBC is HER2-positive, your treatment will probably also include Herceptin for about a year. Femara or another aromatase inhibitor may be added for hormone-dependent tumors. Depending on the nature of your IBC, your treatment may continue from nine months to five years or longer. Some women may need treatment throughout their lives.

Because IBC is often misdiagnosed and has usually metastasized by the time it is discovered, the five-year survival rate is significantly lower than the survival rate for patients with other types of breast cancer. In past years, IBC was treated with mastectomy alone; a treatment that almost always failed. The current approach to use combination therapies has greatly improved the prognosis. Between 30-40 percent of women with IBC now survive five years after diagnosis. One-third survives 10 or more years.

Researchers have made two important discoveries regarding IBC that may help advance our knowledge of IBC and lead to effective treatments: the University of Michigan found that too much of the RhoC GTPase gene in cells can lead to quick-growing IBC tumors. (RhoC GTPase has previously been linked to cancers of the liver, skin and pancreas). Experts hope this discovery will lead to more effective treatments for IBC. In 2007, Dr. Sanford Barsky, Professor of Pathology at Ohio State University, successfully developed an animal model of the disease.

The National Cancer Institute sponsors clinical trials to find new, more effective treatment for IBC. If you’ve been diagnosed with IBC and would like to participate, visit www.cancer.gov/clinicaltrials or call 1–800–4–CANCER.

AUSTRALIA

AUSTRALIA BELGIË

BELGIË CANADA

CANADA DANMARK

DANMARK FRANCE

FRANCE DEUTSCHLAND

DEUTSCHLAND ITALIA

ITALIA NEDERLAND

NEDERLAND NORGE

NORGE REST OF THE WORLD

REST OF THE WORLD ESPAÑA

ESPAÑA SVERIGE

SVERIGE UK

UK USA

USA